A broad perspective on the return of industrial and commercial productivity in the U.K. and determine how sustainable the new trend may be. A comparison of the U.K. and US to highlight the effects of different country-specific factors, with a focus on providing information useful to investors and se

Introduction: The concept of productivity improvements is often gauged through advancements in factors such as efficiency, innovation, and overall performance (Schwab 2017). In an innovation-driven economy like the United Kingdom (UK), fostering business innovation and sophistication becomes pivotal for growth. Efficiency gains are achievable via investments in education, labor markets, financial markets, and more (BIS 2013; Schwab 2017). This article delves into trends and sustainability of industrial and commercial productivity in the UK, comparing it to the US. It explores factors like macro-environment, healthcare, education, infrastructure, and institutions that impact productivity.

Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) Analysis: The Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) analyzes determinants of long-term economic growth, including institutions, policies, and productivity (Schwab 2017). The UK ranks 8th in competitiveness, while the US secures the 2nd spot with scores of 5.51 and 5.85 respectively (Schwab 2017). The UK's competitiveness score improved slightly from 5.49 last year, but the increase was minor compared to the US's 0.15 (Schwab 2017). The UK's competitiveness diminished, with a lower overall rank and modest score improvement compared to the US (Schwab 2017). While the UK experienced a small GCI increase of 0.1 over 5 years, the US showed a stronger improvement of 0.4 (Schwab 2017). However, Schwab (2017) asserts that recent productivity growth is cyclical, driven by low interest rates rather than fundamental drivers, and may not return to historical levels.

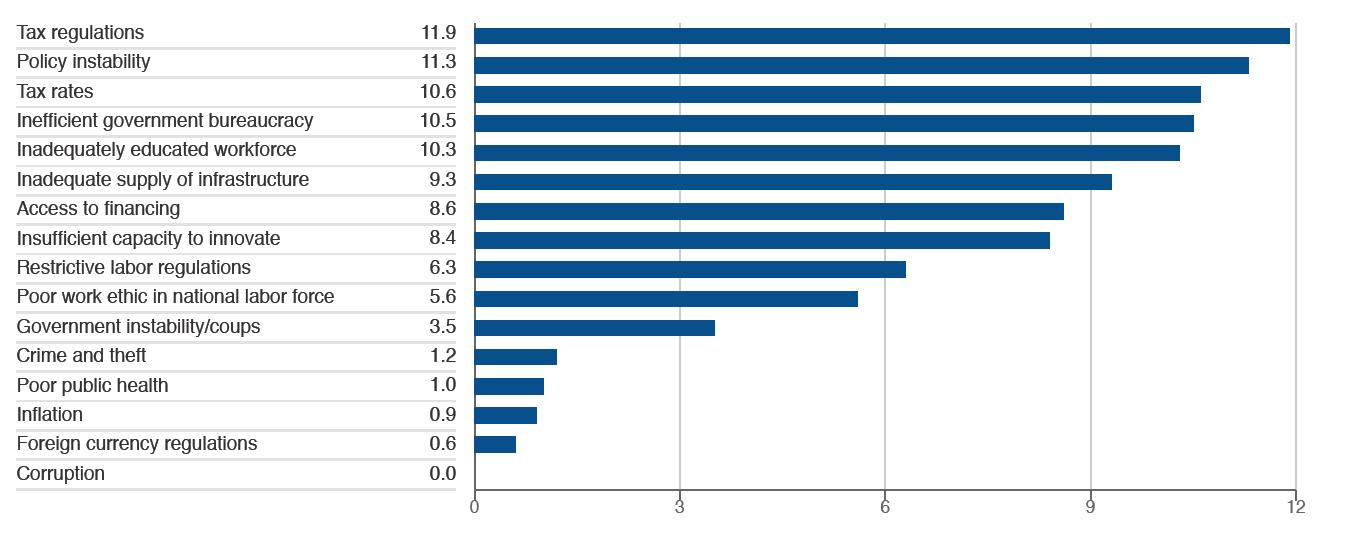

Productivity and Brexit Impact: UK's technological readiness surpasses the US, yet the US has shown recent advancements. The US leads in productivity through innovation, while the UK ranks lower compared to Germany and Japan (Schwab 2017). Schwab (2017) suggests that UK's industrial and commercial productivity may deteriorate post-Brexit due to various factors like tax regulations, policy instability, bureaucracy, education gaps, and inadequate infrastructure (Appendix B). Sustainable growth pillars in the UK encompass research, skills, infrastructure, small businesses, trade, energy, competitive advantage, inclusive growth, and institutions (Samans et al. 2017; Syverson 2011). These avenues can also sustain productivity through investments in education, training, healthcare, and financial markets (Demeter et al. 2011).

US Challenges and Solutions: The US faces macroeconomic uncertainty, emphasizing the need for healthcare, primary education, and institutional development (Demeter et al. 2011). Challenges like restrictive labor regulations, corruption, and infrastructure issues hinder productivity. Even the second-most competitive economy faces concerns over corruption, government inefficiencies, healthcare access, and quality education (UN 2016). Foda (2017) notes weak productivity growth, impacting GDP growth. Advanced economies experienced 0.3% GDP growth from 2008 to 2015, compared to 2% from 1990 to 2007. While labor productivity slowdown linked to low total factor productivity growth, capital deepening had more influence (Foda 2017). Recent productivity gains in the UK and US might not be sustainable and preceded the global financial crisis (GFC) (Foda 2017).

Sustainability Challenges and Automation: Technological disruptions are crucial for sustained productivity growth. While automation holds potential, the pace of technology adoption depends on feasibility, cost, labor dynamics, and more (Bughin et al. 2017). The aging population supports automation's necessity for maintaining living standards. However, UK and US policymakers face challenges in encouraging necessary investments due to concerns over job loss (Bughin et al. 2017).

Manufacturing vs. Services and Skill Development: Diversification into manufacturing can yield growth and stability (UN 2016). However, the services sector dominates the UK, leading to volatility. Matching skill development with technology is crucial for sustained growth (Green et al. 2017). Businesses must adopt technology to counter risk aversion, overcoming structural productivity issues (Frey & Osborne 2013; Bakhshi et al. 2017).

Concluding Insights: Long-term productivity improvement demands synergy between technology and policy. Skill investment and technological integration are vital for sustained growth. Automation, AI, and innovation play pivotal roles. Fostering inclusive growth, sharing gains, and embracing technological advancements are vital for sustained productivity enhancements in the UK and US.

Bibliography

- Abdel-Wahab, M, Dainty, A, Ison, S, Bowen, P and Hazelhurst, G. (2008). Trends of skills and productivity in the UK construction industry. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, Vol. 15 (4), pp. 372-382.

- Baily, M and Bosworth, B. (2014). US manufacturing: Understanding its past and its potential future. Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 28 (1), pp. 3-26.

- Bakhshi, H, Downing, J, Osborne, M and Schneider, P. (2017). The future of skills: Employment in 2030. London: Pearson and Nesta.

- Blaug, M. (2009). The economics of productivity. London: Edward-Elgar.

- Brighton, R, Gibbon, C and Brown, S. (2016). Understanding the future of productivity in the creative industries. London: SQW Limited.

- Bughin, J, Manyika, J and Woetzel, J. (2017). A future that works: Automation, employment and productivity. Brussels: McKinsey Global Institute.

- Business, Innovation and Skills. (BIS) (2013). International comparative performance of the UK research base: A report prepared by Elsevier for the UK’s Department of BIS. London: BIS.

- Demeter, K, Chikan, A and Matyusz, Z. (2011). Labour productivity change: Drivers, business impact and macroeconomics moderators. International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 131 (1), pp. 215-223.

- Foda, K. (2017). What’s happening to productivity growth? Key macro trends and patterns. Washington D.C: Brookings Institution.

- Foda, K. (2016). The productivity slump: A summary of the evidence. Washington D.C: Brookings Institution.

- Frey, C and Osborne, M. (2013). The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Oxford: University of Oxford.

- Gorg, H, Henze, P, Jienwatcharmongkhol, V, Kopasker, D, Molana, H, Montagna, C and Sjoholm, F. (2016). Firm size distribution and employment fluctuation: Theory and evidence. Stockholm: Research Institute of Industrial Economics.

- Green, A, Hogarth, T, Kispeter, E and Owen, D. (2016). The future of productivity in manufacturing: Strategic labour market intelligence report. London: SQW Limited.

- Haldane, A. (2017). Productivity puzzles. London: Bank of England.

- Her Majesty’s (HM) Government. (2017). Building our investment strategy. London: HM Government.

- McGowan, M, Andrews, D, Criscuolo, C and Nicoletti, G. (2016). The future of productivity. Paris: Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development.

- Parpala, M. (2014). The U.S. semi-conductor industry: Growing our economy through innovation. Washington D.C: Semi-conductor Industry Association.

- Purdy, M and Daugherty, P. (2016). Why artificial intelligence is the future of growth? Dublin: Accenture.

- Rodrik, D. (2013). Unconditional convergence in manufacturing. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 2013 (1), pp. 165-204.

- Salazar-Xirinachs, J, Nubler, I and Kozul-Wright, R. (2014). Transforming economies: Making industrial policy work for growth, jobs and development. Geneva: International Labour Office.

- Samans, R, Blanke, J, Hanouz, M and Corrigan, G. (2017). The inclusive growth and development report 2017. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

- Schwab, K. (2017). Insight report: The global competitiveness report 2017-2018. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

- Syverson, C. (2011). What determines productivity? Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 49 (2), pp. 326-365.

- United Nations (UN). (2016). Industrial development report 2016: The role of technology and innovation in inclusive and sustainable industrial development. Vienna: United Nations Industrial Development Organisation.

- UN. (2013). World Economic and Social Survey 2013: Sustainable development challenges. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

- Woodhouse, P. (2010). Beyond industrial agriculture? Some questions about farm size, productivity and sustainability. Journal of Agrarian Change, Vol. 10 (3), pp. 437-453.

- World Bank (WB). (2018). Global economic prospects: Broad-based upturn, but for how long? Washington D.C: WB.

- World Economic Forum (WEF). (2014). Matching skills and labour market needs: Building social partnerships for better skills and better jobs. Davos: WEF.

![General government debt (% GDP) [2006 vs 2016]](https://www.ukessays.com/services/samples/images/business/general-government-debt.jpg)

Appendix A

General government debt (Schwab 2017)

Appendix B

Most problematic factors for doing business in UK (Schwab 2017)

![Trend of labour productivity growth in advanced economies [1971-2015]](https://www.ukessays.com/services/samples/images/business/productivity-growth-advanced-economies.jpg)

Appendix C

Trend of labour productivity growth in advanced economies (Foda 2017)

![Convergence and divergence in labour productivity [1950-1990] [1990-2015]](https://www.ukessays.com/services/samples/images/business/convergence-divergence-labour-productivity.jpg)

Appendix D

Convergence and divergence in labour productivity (US =1)